A voyage in North Africa

Look at this peasant seated in the gentle shade of the dark trunk of an almond tree which loses a handful of white petals at each puff of wind. Well installed on a rustic chair with a glass of wine at hand, he turns a long wooden spoon in a pestle full of egg yolks. Drop by drop, he pours the good pale olive oil and then adds enough crushed garlic to whiten his "ailloli"; a glance to measure the pepper and a drop of vinegar to finish it. That's something that can be eaten with potatoes cooked on the embers and its marvelous.

Oil painting by O.Gonet

And the little world of seafarers?

- Do you know about fishing for tunny? A Spanish friend asked me.

I certainly know about the life on these fishing boats, scarred and battered by the work of the men and by the sea.

- No, no! I mean fishing for them with a net, lets go and see! And off we went.

A village to the South of Cartagena or rather a handful of little whitewashed houses tumbling from below the cliffs as far as the violet sea, where huge blocks of stone thrown at random, form a kind of landing stage.

Floating on the clear water are not more than half a dozen little rowing boats. A few fisherman's families and some good old women wearing tight buns, the size of pigeon eggs on their heads and at school closing time, a handful of urchins with gappy smiles, playing the fool with an old tin can.

We are in June, the tunny-fish season. All the fishermen are placed under the stern authority of Joaquin, the king of Ithaca. He is ageing a bit but is still a proud bearded individual with coal black eyes. He reigns over a little community of fishermen who are almost all related to him. They have put down a little way out from the village, a gigantic net of several kilometers, opened wide to the hoped for entry of shoals of tunny-fish. This net, fixed on the bottom by a number of enormous ships anchors, of the time of the galleons, tapers into a huge string sock.

Now they are waiting, sitting on the quay whispering as if in church. In the distance, one of them is watching motionless in a little boat and that goes on sometimes for a few days and sometimes even for a few weeks.

Suddenly, one morning or one evening, no matter when, the sock fills at one blow with an explosive mass of life. The tunny-fish have arrived.

Then they rush for it. Its a tremendous butchery and then its the village feast. Wine, a guitarist and a bean feast. The king of Ithaca is praised as much as teased by a troop of widows who laugh as if they were going off like a flock of birds.

Alone on the cliff top and in spite of the frenzy of those feasting, the black silhouette of a shepherd has not moved an inch.

The wind which ruffles my hair, chases a trail of clouds across the landscape. Needles of sunlight recede in the distance over a sea shimmering with light.

This is my country. This is what I am trying to paint today and in spite of the passing years, the pleasure is always a new one for me.

* * *

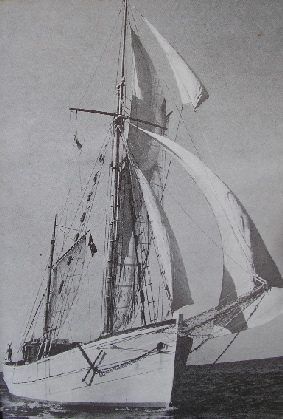

Twenty years ago, in 1965, off the coast of the Libya of King Idris, I was navigating on board an oceanographic sailing ship the Atuana. At that time along with my friend Max and a little crew of seamen and technicians, I was running a programme of deep sea archeological research.

Atuana, mon dear end old sailing boat in Mediterranee

In the famous gulf of Syrte, between Tripoli and Benghazi, bad weather suddenly came down on us.

Ever since antiquity, since Homer and the Odyssey, the bad reputation of the Gulf of Syrte is nobody's business.

In the days of galleys and amphora, it was so distrusted that in the winter, in the bad season, the sailors preferred to pull their boats into dry dock and wait for the Spring. Today even, books of nautical instructions are pessimistic: violent winds raise up a foul sea which is hollow and short and of course naturally so, in wintertime. And we were in January. But what of it, we had to pass through there to continue our voyage and we were already late with our schedule.

When the bad wind comes shrieking at you the waves are suddenly lethal. They graze the whole length of the ship's hull which is lying right over on its side. Down below Béchir, our cook is preparing the dinner but the ship is heeling over to such an extent that he is standing on the wall of the cabin, his back against the flooring which is almost vertical.

And the sea hollows out even more.

The yawing of the vessel now causes

shocks which are at the same time so slow and so brutal that the force cannot be

imagined by someone who has never navigated.

The yawing of the vessel now causes

shocks which are at the same time so slow and so brutal that the force cannot be

imagined by someone who has never navigated.

The saloon cupboards open all of a sudden and vomit out pell-mell provisions, clothes, books and God knows what else.

To put the lid on the whole disaster, a row of bottles of red wine have just smashed on to the whole mix up of objects which are already rolling around the saloon.

Outside, a black sky begins twenty yards above the masts. The rain is horizontal. The problem above all is not to get lost.

Now in the liquid chaos, one cannot see anything. At that time, guiding by satellite didn't yet exist and the sky being completely overcast prevented any use of the sextant. Only radiogoniometry remained and above all the good old navigational method of estimating your position. Unfortunately, with bad weather, there is less precision and after 5OO or 6OO kilometers of sea, the moment arrives when you have to admit that you don't really know where you are; and its a very unpleasant thing to have to do on a ship lost in bad weather.

I can remember the hours passed in front of our gonio apparatus, hunting for signals of radio beacons. It was a big gray metal object. Two greenish dials looked stupidly at me. At the side was the earpiece hanging from a black bakelite telephone, worn out by the salt.

In the middle of the third night, we finally got the Benghazi transmission and it was by following its direction and listening to it growing in volume that finally someone saw the entrance to the harbour through a curtain of rain.

It is a wonderful pleasure which is always new, arriving in a sailing ship from the huge empty spaces of the sea and seeing various details on land which always seem to be lost out in the vast ocean. Besides it is a pleasure as old as seamen's craft. During the voyage, the sea can have been difficult or friendly, life on board monotonous or violent but the outlook on arrival always brings the same feeling of exultation.

Once the anchor is dropped and well hooked on the seabed and the canvas down and furled on the booms one rushes on shore to see the people and the trees and things and to hear, feel and drink in the life that seems to hit one in the face.

But first of all, one always has to go through the customs.

A little bunch of wild daisies stuck into a tooth glass decorates the table of the fat civil servant who drives us mad with his official questioning. Showing the tip of his tongue and observing very carefully the margin of a school exercise book ruled with sky-blue lines, he writes down our answers with a metal nib at the end of a wooden holder all worn away with his hesitation. Behind him, a little wall of paper seems to be building up. A sort of pavement of exactly the same sheets of paper, which are the answers obtained from all the boats which have come in before us since God knows when. This is one of the inconveniences of Mediterranean culture. The taste for laws and lawyers and civil servants is stronger than elsewhere. The great flabby buttocks of the statue of the scribe seated 4OOO years ago at the entrance to Tutankhamons tomb are always lukewarm and alive even in modern administration.

A few days later, we took to the sea. To the East of Benghazi which is a fairly large town marked out with minarets, the last houses and the last dustbins are lost in the desert which is beginning. It is a desert of crumbling rocks and stoney sands. On places a few dried up bushes mark the ancient bed of a river dead long ago. The romantic aspect which an adventure sometimes involves rather went to my head. Like a symbol of happy life the ship veered, heeling over tentatively. A slow pitching and the lovely sound of the violet blue waves which break into foam along the hull. I went to stretch out on the net which is suspended under the bowsprit and there I listened to the roaring of the stem as it carved its way.

Over my head was a cloud of some 18O square meters of white sail, a complicated scribble of cordage and a mast which grated as it leant over beneath the gusts of wind.

The simple joy of navigation in good weather. The ship stands off a little from the coast and the land is a blur on the horizon. There is nothing but the violet sky and the still more violet sea.

A few hours later, the land reappears and we soon see the smiling white ruins of Apollonia. It is thither that we are going.

In the time of the Greeks, Apollonia was the rich port of luxuriant Cyrenaica. Today, the town is long dead and the ancient colony once the pride of aristocracy is nothing more than a huge white and solitary desert. But the poetic force of this place takes your breath away.

First of all there are the massive harbour walls. They protect the green waters of a fairly large lagoon, out of which emerge three hills covered with ruins. They are built of such a dazzling stone that you would say they have just been whitewashed.

On the top of each hill there are the white remains of a dead temple. In the course of millennia, the Lybian coast has undergone extremely slow geological movements. Here a slight sinking took place. Several meters of collapse beneath the level of the Mediterranean. The three hills which once dominated the town of Apollonia are no more than three little islands surrounded by water. All the remainder has been inundated.

At the side of one of the islands there is a sort of chalkey trace where a gigantic bite has been taken out. The ruins of an old amphitheatre shaped like a half-moon. Evidently it has also partly subsided under the waters but the upper part of the tiers are still visible. It forms a sort of little creek well sheltered from the wind. It is there, at the center of the scene, that we have dropped anchor.

The ship as if surrounded by absent

spectators is poised above its shadow.

The ship as if surrounded by absent

spectators is poised above its shadow.

Just at the side of the theatre, some streets come out of the sea and continue along the waterside and climb the hill and end near an arrangement of white columns standing on a broken carpet of mosaic. It is one of the three temples on the hills. An atmosphere of extinguished noise, of motionless rumbling. Under the water, the scene continues. Streets, shops, workrooms of artisans. Whence shoals of fish dart out. The main part of the town is flooded and is probably buried under the sand of the lagoon but some quarters have been protected from wear and tear by the mass of the ruined harbour.

It is a harbour of the Phoenician type. Like at Tyre, on the Lebanese coast, it is divided into two well separated parts, the one normally open on to the sea, the other smaller and surrounded by defensive walls against the enemy invading from the sea. It is there at the bottom of this second harbour that the installations for repair and winter storage of boats is marvelously well preserved. The gulf of Syrte is quite near. The ancient galleys awaited the end of the winter here before risking to go out.

Apollonia, a dead town, capital of a dead land and yet, coming from God knows where, a dozen proper ruffians seem to be watching us from a long way off. Useless to get involved, night is falling it is better to take shelter in the boat, listening to stories from Béchir, our Tunisian cook.

We engaged him a few weeks earlier, when taking a turn round the "Café de Paris et des Colonies" in Tunis. He is a little chap, completely gray, apart from his chin which sports a beard.

During all these evenings beneath the stars, just beside the dark fringe of the ruins of Apollonia, he tells us without knowing it, stories which have come straight out of the Old Testament.

A Moses dressed in a djellaba who crossed the Red Sea thanks to the miracles of Allah!

There was also the story of a kind of Tunisian Herodotus who discovered the pyramids of Egypt without knowing that they were tombs. And then endless tales of Saharan warriors.

Years have passed since our evenings on board the ATUANA anchored in the amphitheatre of Apollonia. Only a few images still remain in my memory. The one of a marvelously pure and beautiful princess. Béchir told us that she had a sex which resembled the imprint of a gazelle's hoof on the sands of the desert. And all the while a great goose of a harvest moon was rising on the horizon. In this new gleam of light, the Smokey lamp on the deck didn't shine any brighter than our glasses of red wine.

|

Portrait of Bechir

drawings by O.Gonet

The island of Cyprus, May 1967.

Midnight was sounding when, some months later, we dropped anchor in a little creek to the South of the island of Cyprus. We were arriving straight from the open sea and were pretty tired. A night of sleep was necessary before confronting the customs in the port of Famagusta, the ancient capital and chief port of the island.

Five minutes later, all were asleep on board.

At the hour of the first damp glimmer of dawn, a shock against the hull woke us with a start. It was a little rowing dinghy manned by a great ungainly fellow with an enormous moustache, trembling with fury. There he was raging at us in a language as harsh as it was incomprehensible. The clearest thing in this torrent of fury was the finger that he pointed in the direction of the open sea. He wanted to see us clear out as soon as possible.

Pierre, our photographer from Zürich, who doesn't take to being woken with a start, sprang on to the bridge in an excited state and poured out a torrent of abuse at him in pure Swiss-German. On his little boat, the noble Cypriot remained dumb with stupefaction.

His anger cooled down, he explained to us in rudimentary English, that, by chance, we had dropped anchor plumb in the middle of the line which separates the Cypriot Greek partisans from the Cypriot Turks. The one lot are on the right bank and the others on the left bank. At sunrise the war will start again and we shall be causing trouble.

Alright so we let these gentlemen cut each other's throats in the way they understand and we go off and tie up in the harbour of Famagusta.

Famagusta is a strange mixture of Greek village and Turkish market and English Colony.

The English in shorts with a cap like a soup plate upside down on their heads, endeavor in a friendly way to separate the Muslims from the orthodox who have detested each other for centuries.

* * *

We have come to Cyprus to examine the geological structure of the sea bed. For this reason we have chosen to moor up on the north-west of the island in the very beautiful bay of Krisokhou.

Apart from its shakey political organization, the island of Cyprus is charming, the beaches lined with foam as Homer said. Besides he said it was the isle of the goddess of beauty.

A couple of paces from our mooring, behind a curtain of pine trees on the cliff, one comes to a village. When we come out on to the square, mouths and moustaches gape with astonishment.

Strangers!

Life just stops. We are the annual event of this small world where nothing ever happens.

Three round tables and a few rustic chairs are lined up in a bistro. The light trotting of little donkeys, hidden under considerable loads of vegetables, shake the glasses of anisette which the waiter, a proud old man whose trousers bottom hang down to his knees, has just placed in front of us.

|

Portrait of a peasant woman met in Cyprus

drawings by O.Gonet

A trifling wound, which I had made under my thumbnail, had become infected and for a week had been ripening into a horrible red and burning whitlow. I was suffering all the more because for some reason or other, each gesture made me knock my bad thumb against any sharp object near my hand.

Brandishing my thumb under the nose of passers-by and carefully articulating a few words of colonial English, I tried to find out about possible medical aid. A miracle, there were two doctors in the village. One here and the other over there, and both had apparently rescued the people I asked, from certain death.

I chanced it and chose the one who lived nearby and following muddled geographical directives, I ended up in a charming little wooden shack which stood somewhat crazily in a garden of weeds. Just at the entrance, Monsieur Seguin's goat was browsing round its tether.

It was definitely there and what was more, the learned old man in spectacles who welcomed me had without doubt the look of competent gravity associated with the medical profession. To say the truth his consultation room looked like my grand-father's tool-shed. A beaten earth floor and a smell of sacks of potatoes. Nevertheless there was an enamelled basin on a table and a real human skeleton hanging by the neck from the hasp of the one and only window. I couldn't understand anything he said. I was terrified of hearing words to do with "purge" and "bleeding", but no, he finally decided on a reasonable injection of penicillin.

After having presented my buttocks to the syringe, I invited him to celebrate my future recovery at the bistro in the square, whither he accompanied me with enthusiasm. Perhaps he used the occasion to show his village clients that even foreigners came to consult him.

A few days later, as there was no improvement at all, I decided to give the other practitioner a try! On arrival, I discovered him behind his house, a nude and powerful torso, occupied with athletic exercises. He was lifting enormous dumbbells and grunting. As I applauded politely, he took advantage of my presence to force his talent a bit in order to lift with one arm what normally needed his entire strength. An unreserved fellow that chap, he practiced medicine with a joy. My whitlow so swollen that I could feel my heart beating, made him roar with laughter. With his enormous hand on my shoulder, he led me straight in to his surgery where armed with a pair of dressmaker's scissors, he cut straight into the quick. A jet of pus sprayed up to the ceiling, but I was cured at that instant.

Thursday, market day in the village. The little donkeys loaded with amphora of wine, trot in the dusty square.

Under the Romanesque vaults of the house-fronts a row of old matrons with black kerchiefs, are laughing and cackling with all their toothless gums. Seated well in the shade, they offer the customers onions, watermelons or goats cheeses which they have placed right on the ground under a handkerchief.

To one side some large tom-cats, their stomachs full, sleep on the remains of fish. Round the three tables at the bistro, men are nobly drinking black tea over a game of dominoes.

ll:00 a.m. The scene becomes enlivened, the dentist has arrived. There he is up on his cart which is all decorated and covered with advertisements. Tweezers in hand, he takes care of his reputation, boasting of his professional lightness of touch. Painless extraction, you feel nothing and to demonstrate he makes in the air a gesture of marvelous facility.

Round his cart, he has placed an array of baskets full of dentures of all sizes. Guaranteed to be real teeth. An assistant helps to try them out, and the choice made, he holds a mirror to judge the effect of the brand new smiles.

Behind the quack, at the back of the square, a little orthodox church can be seen through the branches of an enormous eucalyptus. Inside it is all dark and cool. A few old women in dusty worn out shoes, mumble prayers in front of a candle.

* * *

On board the ship, the scientific work went on, monotonous like most scientific work. Thousands and thousands of numbers read on the dials of our measuring apparatus. Numbers which had no immediate interest. They would only make sense later on, reported on geophysical maps or digested by computers.

Luckily it was also necessary to dive very often to verify the smooth working of the apparatuses which we dragged behind the little motorboat or to unhitch them when they got stuck between two fibrous rocks.

Diving like this we had noticed quite close to the ship a sort of underwater cliff made entirely of the remains of broken amphora. It was a real solidified pudding, several meters thick and stretched out over several kilometers and it certainly represented a very great many broken amphora for such a small region.

Several weeks later, I left the ship temporarily to give a lecture in London on the result of our work in Libya and by chance, I also spoke of this old crockery accumulated under the water near the island of Cyprus. A young English archaeologist was interested in this matter and asked questions about it which were far too learned for me. I got out of it by simply inviting him to the ship so that he could see for himself what it was all about.

After our arrival in Cyprus, he started to work on this strange pudding, filling his cabin with endless samples carefully numbered. And it was he who finally explained to us the meaning of this ancient underwater rubbish heap.

It is necessary to know that the agricultural reputation of the island of Cyprus goes back to antiquity but the island is subject to droughts which in the time of Homer were already the despair of market gardeners. On the other hand, just opposite and fifty miles to the North, the Turkish coast which is very poor and almost uninhabited, receives an abundant supply of water from the rivers which come from Anatolia, only to lose themselves stupidly in the Mediterranean. There fore since the beginning of civilization a stream of importation of fresh water exists between Turkey and Cyprus. Water transported by rowing boat and, of course, in amphora.

|

drawings by O.Gonet

In antiquity, the amphora were probably not a very costly form of container but nevertheless they involved the exploitation of mines of good quality clay. Now, without being rare, these mines are not very common along the coasts of Mediterranean which is relatively dry. Further it needed the work of a good artisan to fire the clay and then there is the wood which also costs something. Finally, it was necessary to transport and sell the new amphora. In short, without being costly, they had to represent a certain amount of capital. Then, of course, as would be the case today, reasonable people would try to make them last. At first they were only used to transport the more noble and costly products, oil or wine for instance. Unfortunately, after several voyage, they smelt of vinegar or rancid oil. So then they were sold off cheaply, to a miller for instance, to carry grain. And then when they had lost a handle or the neck was broken, the miller sold them again. And so on until they ended up all dirty and worn out and in a bad state, on the Turkish coast, where they were sold again and this time for practically nothing to the Cypriot oarsmen who had come to look for fresh water.

Fifty miles of rowing to return to Cyprus, is not all that much, but still it had to be done and the galleys were much less heavy to row when the hold was empty. Then once the fresh water had been poured on to the Cypriot vegetables and in order to avoid the trouble of having to return the heavy old things back to Turkey where they were worth practically nothing one simply pushed them over board.

This went on for centuries, a long enough time to accumulate a real underwater cliff of debris.

I have received recently the book which our English friend published on the subject. He used samples which he had collected with such enthusiasm, so as to identify the origin of the amphora. Near the neck or on the handle or at the bottom of their big bellies, the amphora fairly often bear a seal or just a simple mark which is the signature of the artisan who made it or of the trader who ordered it. By carefully noting all these indications and comparing them to other data know to Mediterranean archaeologists, he succeeded in reconstructing a part of the great commercial lanes of antiquity

* * *

It had been pre-arranged that after some months in Cyprus, our ship should pass through the Suez canal to undertake a programme of scientific research on the tropical coral of the Red Sea. But first of all, we had to go to Beirut to have the hull cleaned and repainted.

At this time, in the sixties, Beirut was still the capital of a happy Lebanon, hospitable and proud of a luxury unsurpassed in the middle- East.

After the bucolic charm of our anchorage in Cyprus, the din of the great harbour of Beirut seems crazy : The syren of the cargo-boats, the grinding of the cranes, the work of the naval dockyard, the blows of the sledge hammer on the hull, a welder's little glowing sun, the agony of a saw on metal. And then the Arabs in pyjamas cursing each other in the heat of the day, a handful of little boys, all of them naked, shouting as they push each other into the dirty water of the harbour, leaving on the stone quay the wet imprint of their tiny little feet.

Behind the naval dockyard, there is the roar of the great modern city, scintillating with multicolored publicity. Buildings of innumerable floors. In the depths of the canyon formed by the geometric facades, a torrent of vehicles, of trams clanking beneath their sparks, of bars vibrating with musical rhythms and of restaurants, imitation oriental-style in the Orient.

In this mechanical ebullition, a mule unperturbed with an old sack under his backside to collect the manure, pulling a cart with wheels of an old car and lying on the load, his master, cap over his nose, is sleeping with closed fists.

And beyond the great city, there is the eternal silence of the vast Lebanese mountains. The ancient world of Phoenician heroes and of the men who cut the white stones.

Here the dream is mingled with the smell of lemon trees, of the boat which is being repainted and of oriental spices.

These smells are timeless. Antiquity must have smelt of lemon and of the paint of boats and of the fish market.

This evening, we celebrate, the boat is ready, tomorrow morning we set out again for Egypt and the Red Sea.

|

drawings by O.Gonet